Category: Web

-

May 9, 2025 | Business, Identity, Web

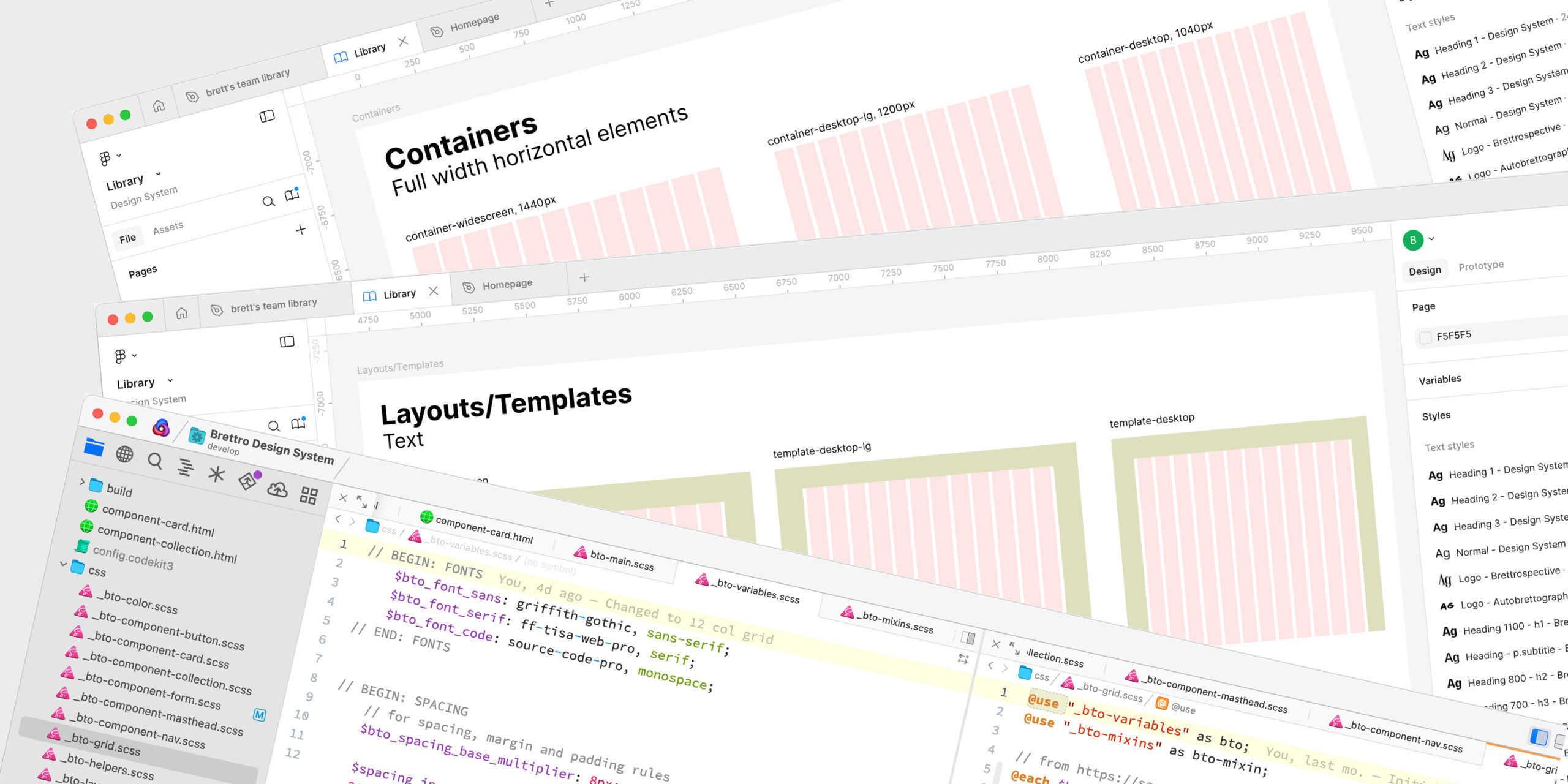

Brettro Design System: Containers & Layouts

Read how I developed my content and page containers and began my layout templates.

-

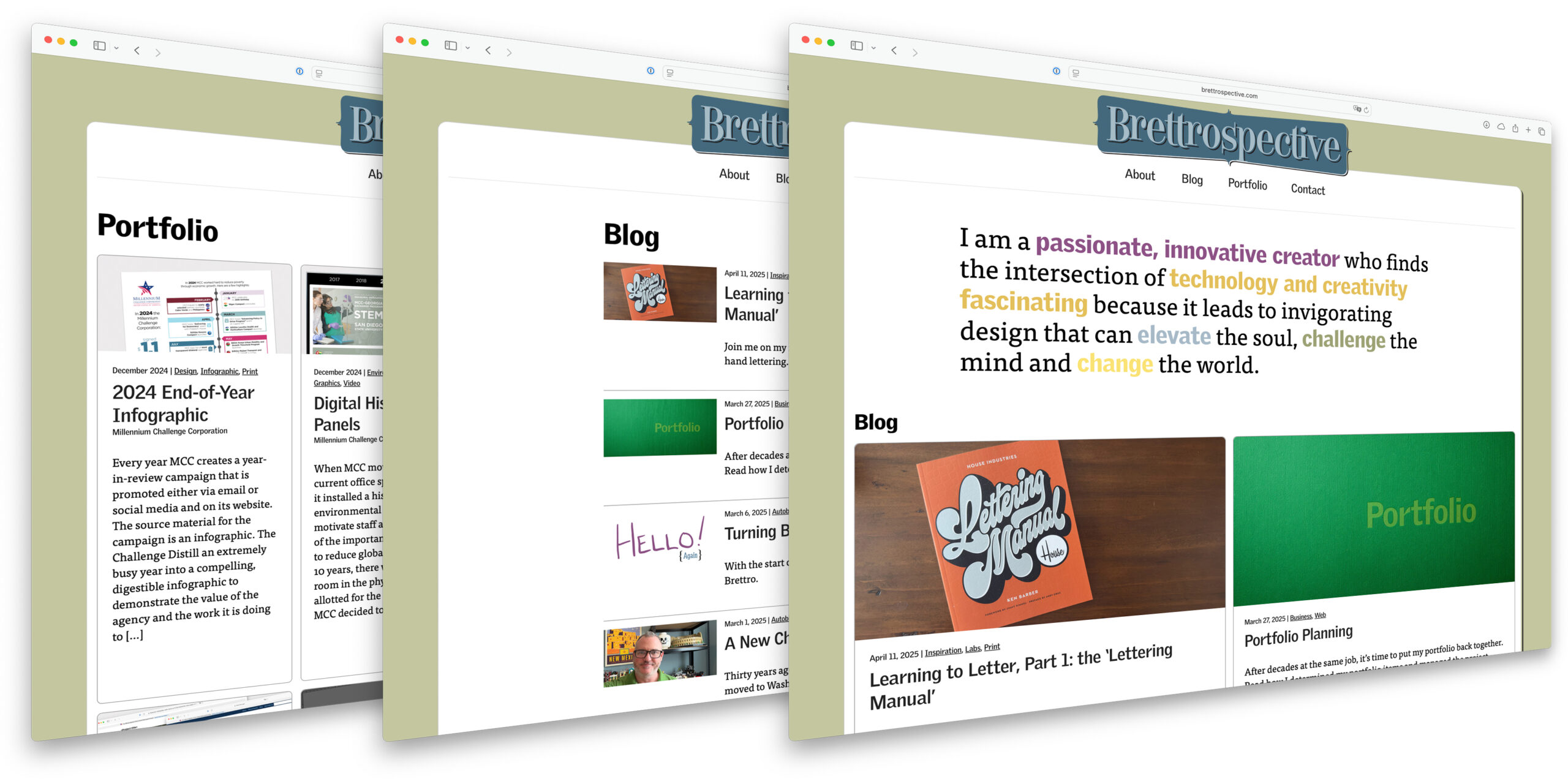

I have finally launched my website’s latest custom WordPress theme bringing years of “the bland Brettrospective” to an end.

-

March 27, 2025 | Business, Web

Portfolio Planning

After decades at the same job, it’s time to put my portfolio back together. Read how I determined my portfolio items and managed the project.

-

January 2, 2025 | Business, Web

Update 2: The Bland Brettrospective

A brief update on Brettro.com’s design.

-

December 5, 2024 | Business, Identity, Web

Brettro Design System: Typography, Part 1

I love typography and was very excited to tackle this aspect of the system. Read how I tackled it and dealt with some frustration about it.

-

November 7, 2024 | Business, Identity, Web

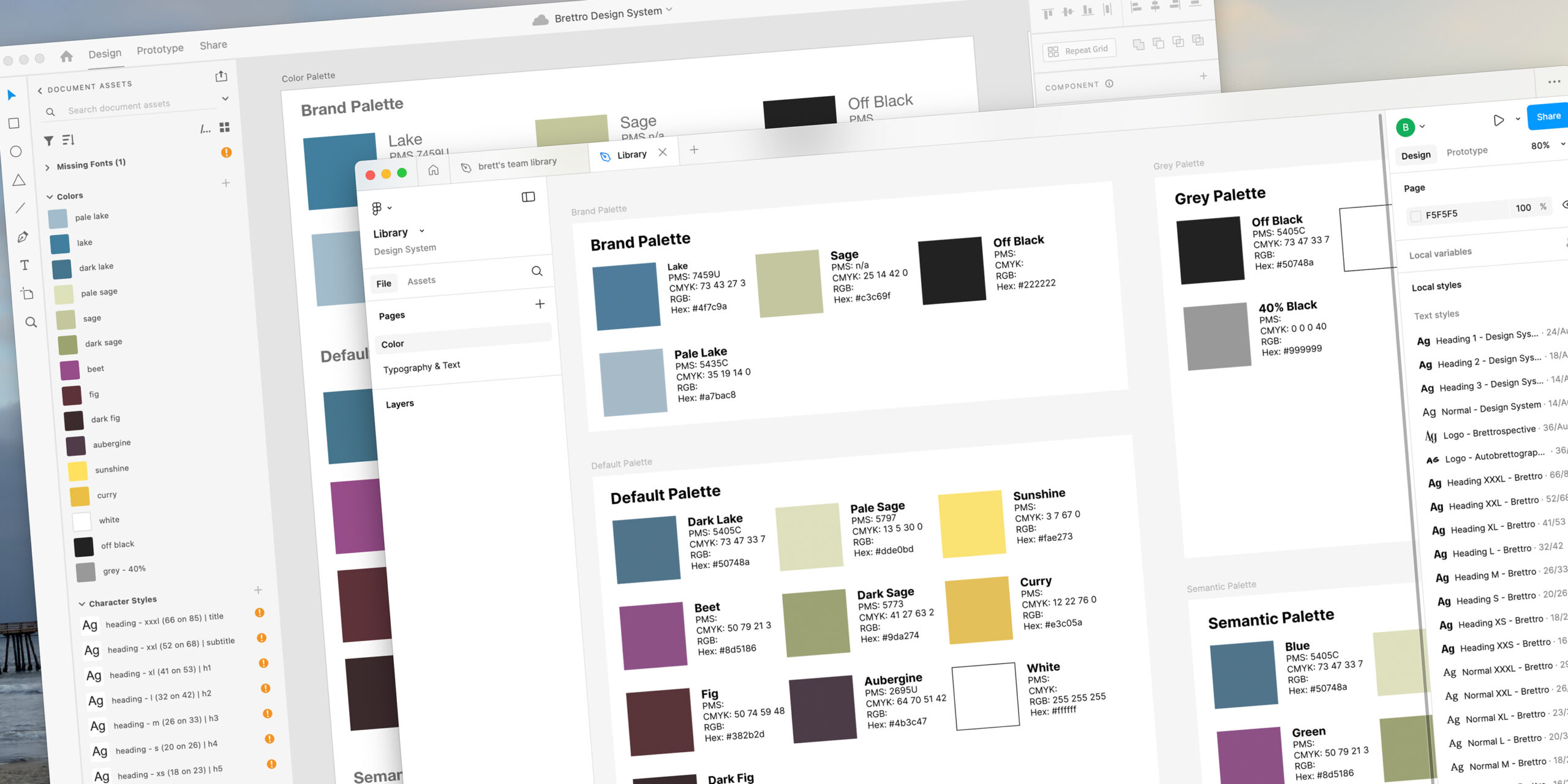

What is all the Figcitement?

About a month ago, after hearing more and more about Figma, I started using it to manage my design system.

-

July 8, 2021 | Business, Identity, Web

Brettro Design System: Grids & Spacing

Learn how a few foundational decisions set up design system spacing and grids.

-

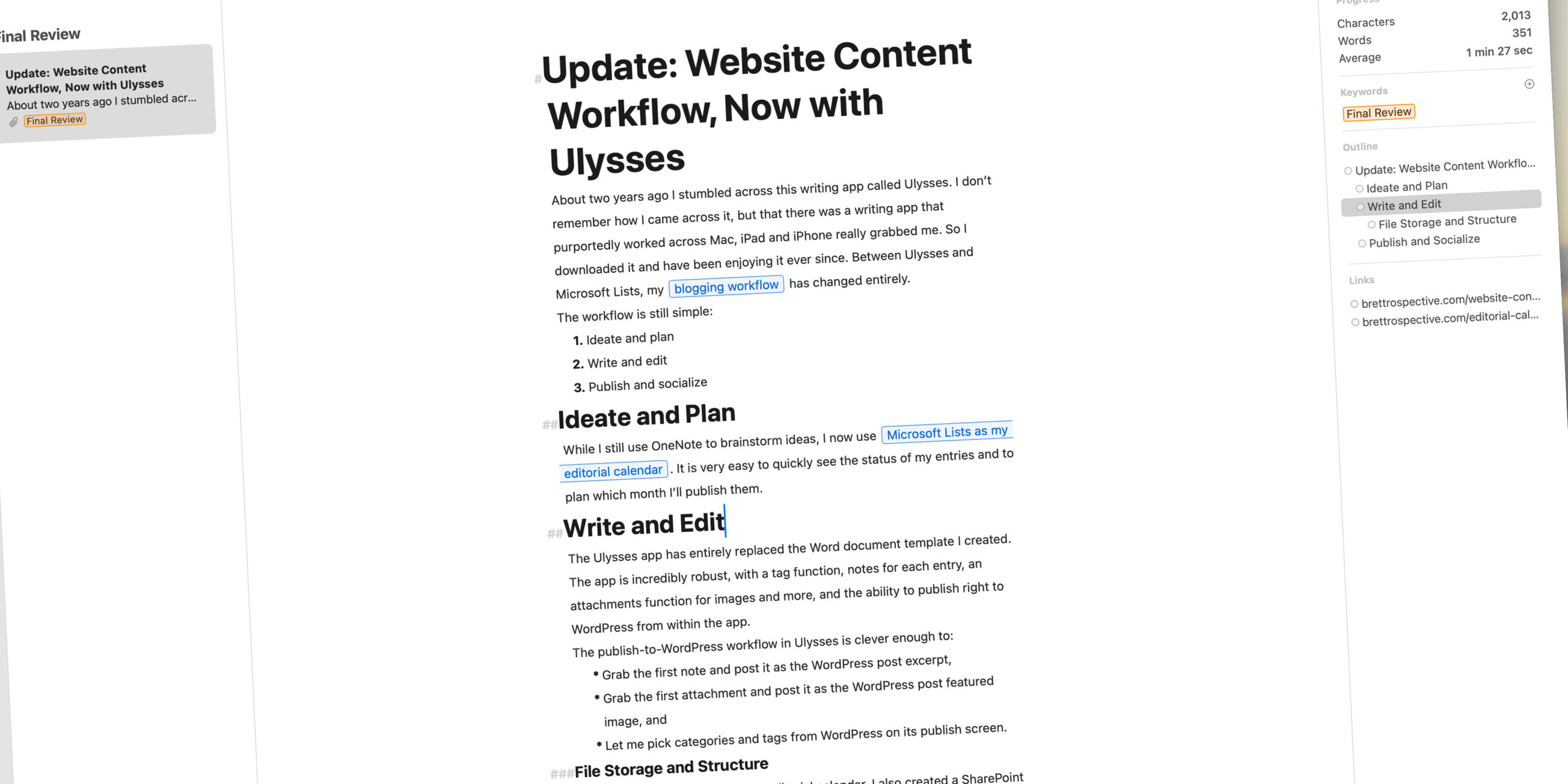

A few years ago I came across Ulysses, a writing app that streamlined my entire content workflow.

-

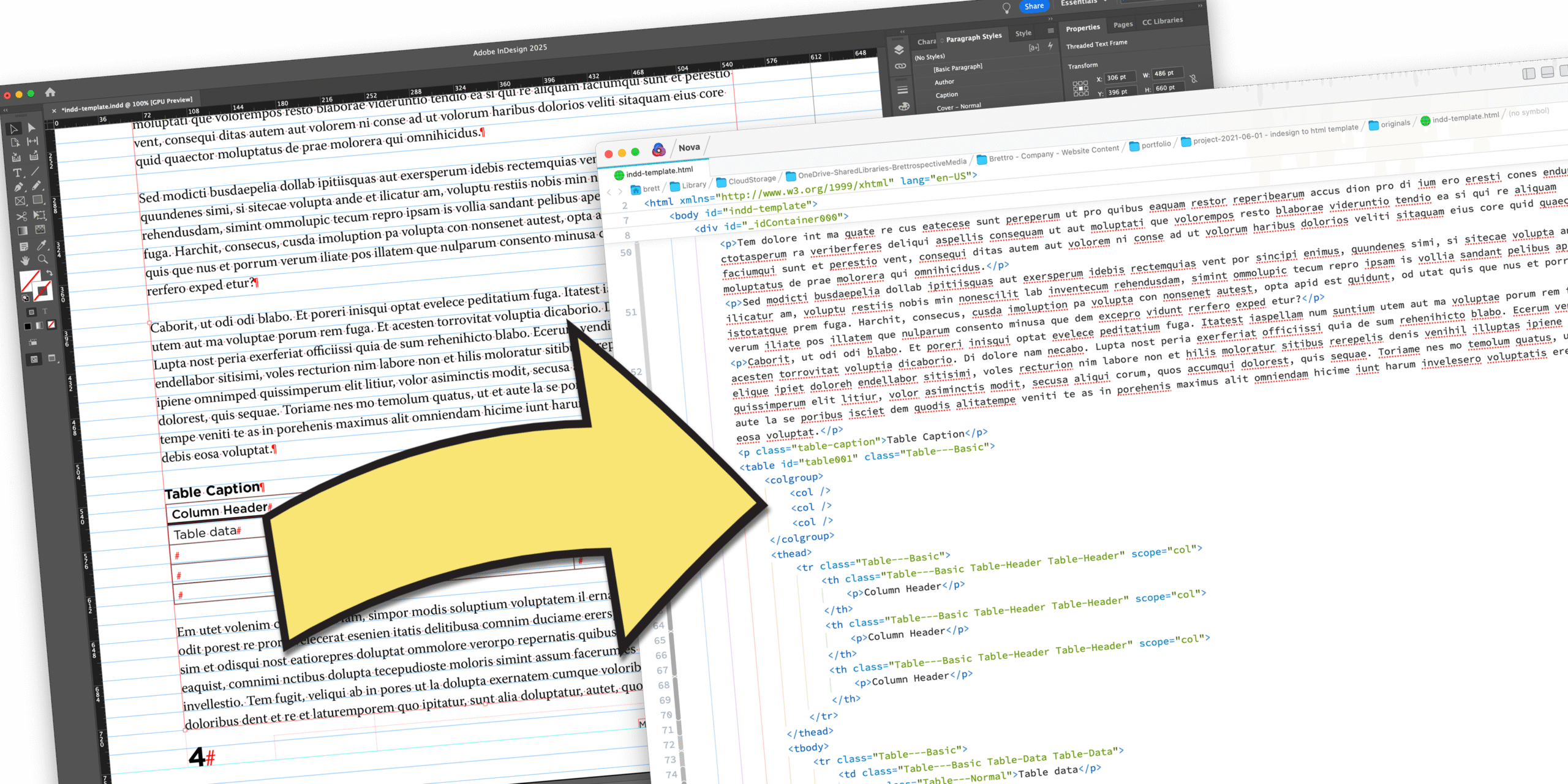

May 7, 2021 | Labs, Print, Web

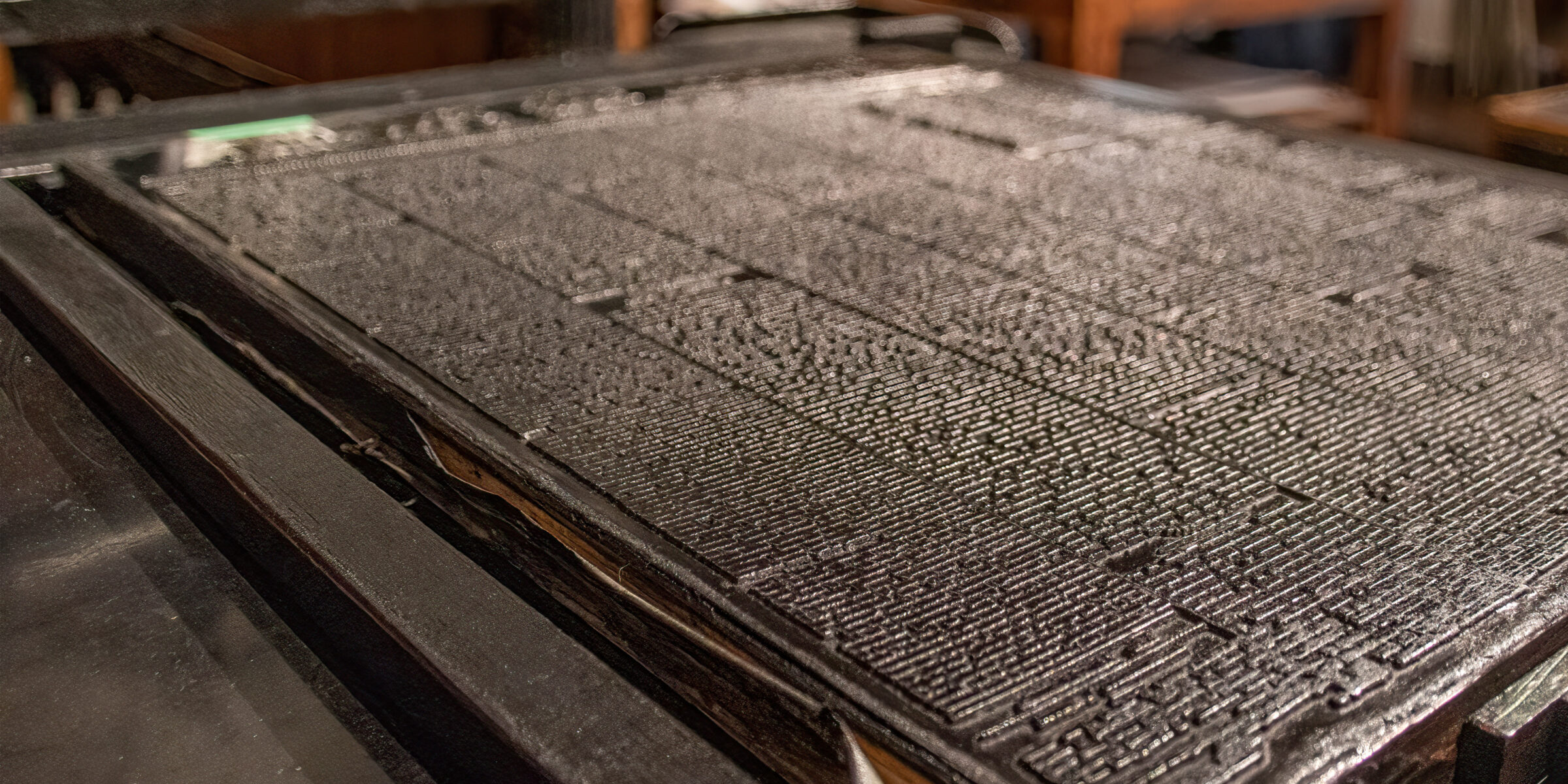

Exporting InDesign to HTML: The Complete Workflow

The final entry of a multi-part series doing a deep dive into Adobe InDesign’s Export to HTML functionality with this post focusing on the complete workflow.