Category: workflow

-

March 27, 2025 | Business, Web

Portfolio Planning

After decades at the same job, it’s time to put my portfolio back together. Read how I determined my portfolio items and managed the project.

-

November 7, 2024 | Business, Identity, Web

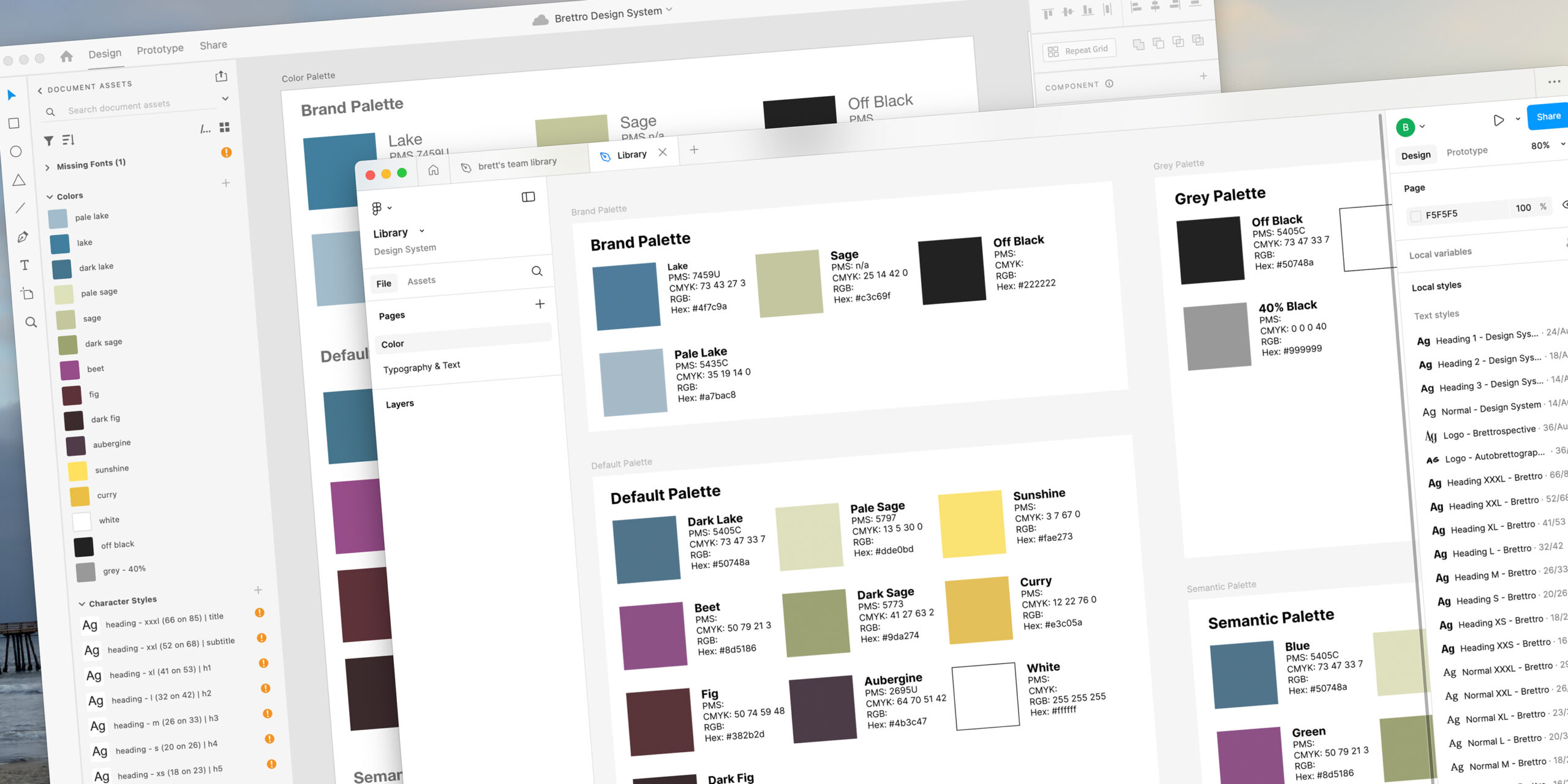

What is all the Figcitement?

About a month ago, after hearing more and more about Figma, I started using it to manage my design system.

-

July 8, 2021 | Business, Identity, Web

Brettro Design System: Grids & Spacing

Learn how a few foundational decisions set up design system spacing and grids.

-

March 4, 2021 | Labs, Print, Web

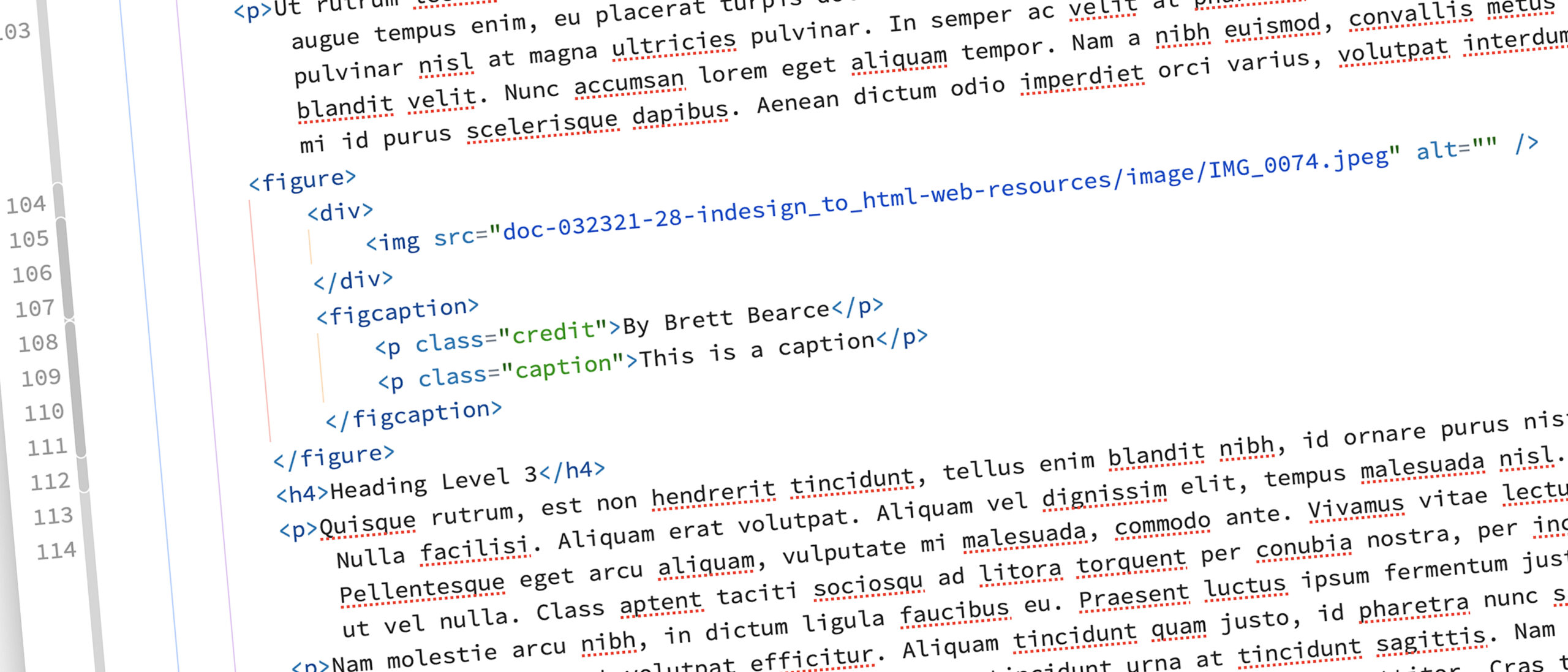

Exporting InDesign to HTML: Images

The third of a multi-part series doing a deep dive into Adobe InDesign’s Export to HTML functionality with this post focusing on images.

-

February 4, 2021 | Labs, Print, Web

Exporting InDesign to HTML: Tables

Part two of a multi-part series doing a deep dive into Adobe InDesign’s Export to HTML functionality with this post focusing on tables.

-

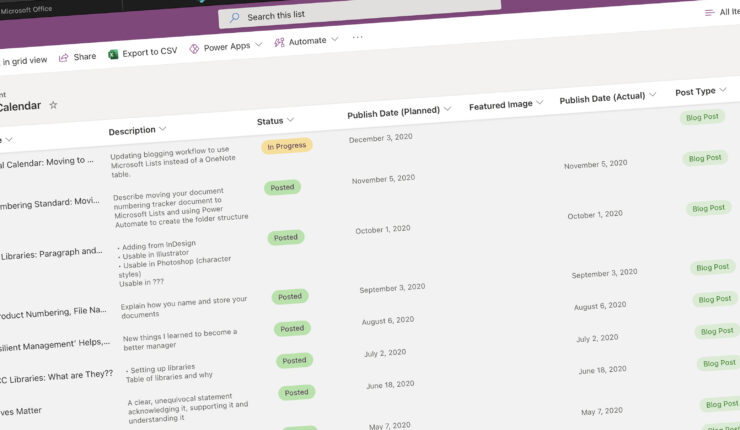

December 3, 2020 | Business

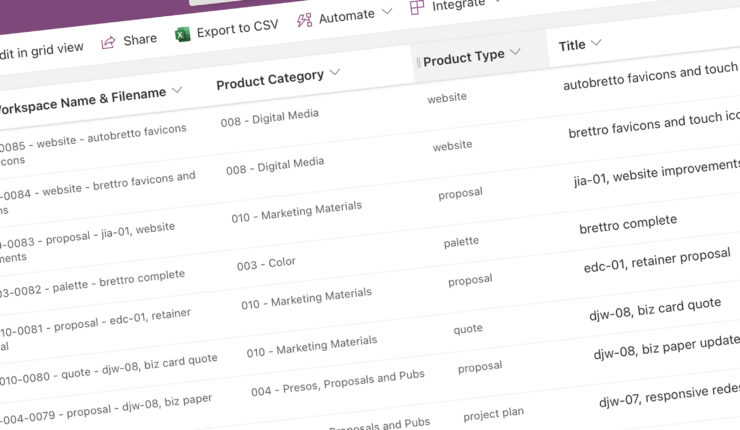

Product Numbering Standard: Moving to Lists

After seeing the value of using Microsoft Lists for my editorial calendar, I decided to use it for managing my product numbering standard.

-

November 5, 2020 | Business

Blogging Workflow: Moving Editorial Calendar to Lists

When Microsoft released Lists this past summer, it’s built-in content scheduler template looked like a great replacement for my OneNote table.

-

October 1, 2020 | Business

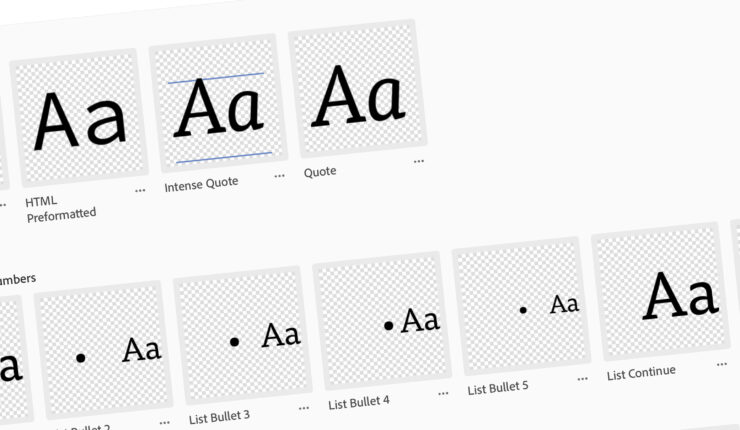

Adobe CC Libraries: Paragraph and Character Styles

After integrating Adobe CC Libraries into my design workflow it’s clear to me that its most powerful feature is the ability to store paragraph and character styles.

-

September 3, 2020 | Business, Identity

Brettro Product Numbering, File Naming and File Structure Standards

For years I wrestled with how to name and where to save my creative files. And then I came across “Designing Brand Identity” and my light bulb went off.